The Raymond Davis Case A Story of Violence Diplomacy and Controversy

The Incident: January 27, 2011

Raymond Davis, a former U.S. Army Special Forces soldier turned private security contractor, found himself at the center of an international firestorm on a seemingly ordinary day in Lahore, Pakistan. On January 27, 2011, Davis was driving through the bustling streets of the city, a place he had grown familiar with during his time providing operational security in the region. In his book The Contractor, Davis describes this moment with vivid detail: he was stopped at a traffic light at Muzang Chowk when two young men on a motorcycle pulled up in front of his vehicle. What happened next would change his life—and strain U.S.-Pakistan relations to the breaking point.

According to Davis, one of the men, later identified as Faizan Haider, brandished a pistol. “As soon as I saw the gun’s muzzle moving in my direction, I unclicked my seatbelt and started to draw the gun,” Davis writes (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 14). A veteran trained in high-stakes situations, Davis prided himself on his speed—his fastest draw time was 0.95 seconds, a skill honed over years of military and contracting work. He drew his Glock 17, a weapon issued to him upon arriving in Lahore, and fired. In a matter of seconds, both men—Faizan Haider and Faheem Shamshad—lay dead on the street. Davis claims it was self-defense, asserting that the men were not mere robbers but possibly operatives with malicious intent, though he offers little concrete evidence beyond his own account.

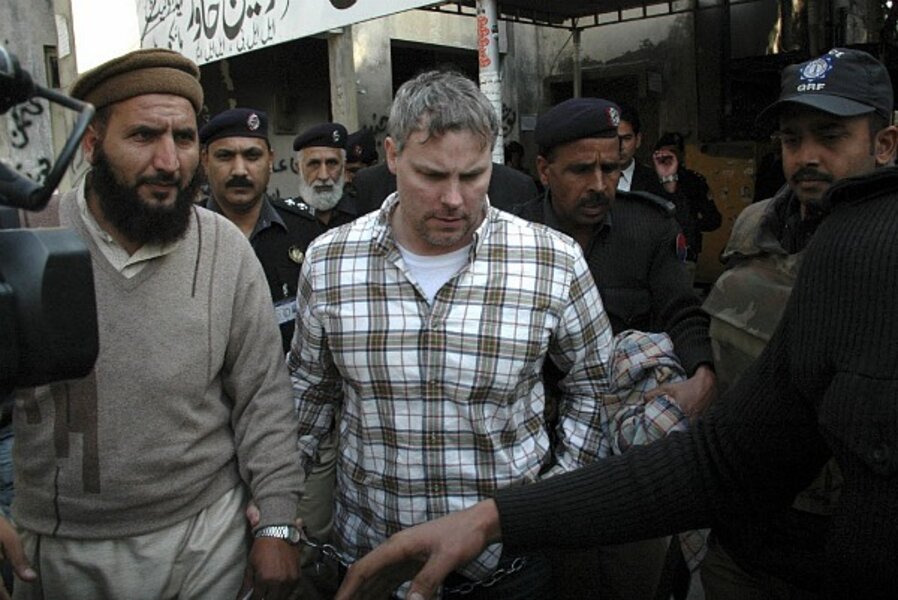

Panic ensued. A crowd gathered, and Davis, aware of the escalating danger, attempted to leave the scene. But the situation worsened when a Toyota Land Cruiser, rushing to extract him, sped down the wrong side of the road and struck a motorcyclist, Ibadur Rahman, killing him. The vehicle fled, leaving Davis alone to face the consequences. Pakistani police arrested him shortly after, confiscating his gear: a Glock 17, a camera, a phone, and a Motorola two-way radio—items he says were standard for his role as a contractor.

Imprisonment: 49 Days in a Kafkaesque Nightmare

Davis’s arrest thrust him into Pakistan’s legal system, which he describes in The Contractor as a “Kafkaesque” ordeal (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 87). Held in a Lahore jail, he faced intense scrutiny and threats—not just from authorities but from a public baying for his execution. Charged with double murder, Davis was interrogated repeatedly during a 14-day remand period. He writes of the uncertainty and fear: “Nothing could prepare me for being a political pawn in a game with the highest stakes imaginable” (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 5). The Pakistani media painted him as a cold-blooded CIA operative, while the U.S. government insisted he was a diplomat with immunity.

In the book, Davis reflects on his military background to cope with captivity. Born in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, he had spent a decade in the Army, including six years in Special Forces, before an injury forced him out in 2003. His experience as a contractor in Afghanistan and Pakistan had taught him to accept the possibility of death, but the political machinations surrounding his case were a new battlefield. He hints at past missions—like a tense standoff while protecting Hamid Karzai in Afghanistan—but remains cagey about his exact role in Pakistan, stating only that he was a “private defense contractor” (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 103).

The Diplomatic Crisis

The incident ignited a diplomatic crisis between the United States and Pakistan, already strained allies in the War on Terror. The U.S. claimed Davis had diplomatic immunity due to his diplomatic passport, a stance Pakistan rejected. In The Contractor, Davis notes the public outcry: “The Pakistanis wanted me to hang” (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 62). Protests erupted, and figures like Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi resigned rather than grant immunity, reflecting the domestic pressure on Pakistani leaders.

Behind closed doors, negotiations intensified. Davis recounts rumors of high-level talks, including a meeting in Oman between CIA Director Leon Panetta and ISI chief General Ahmed Shuja Pasha (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 189). The breakthrough came via Sharia law’s provision of diyat—blood money. On March 16, 2011, after 49 days in custody, Davis was brought to a courtroom. The families of the three victims—Haider, Shamshad, and Rahman—accepted $2.4 million in compensation, reportedly facilitated by the ISI and U.S. officials. Davis describes the scene: “The judges waited for signals… I was ‘forgiven’ by the families” (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 195). He was acquitted and immediately whisked out of Pakistan.

Aftermath and Reflection

The resolution left a bitter taste on both sides. In Pakistan, it fueled outrage over sovereignty and accusations of a sellout, with some claiming the military and government had bowed to American pressure. Davis, in The Contractor, expresses frustration at being a “footnote” tied to this incident forever, yet he offers little clarity on his mission, leaving readers to speculate (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 209). He portrays himself as a patriot caught in a geopolitical chess game, a “silent servant” whose story counters the “misleading or downright false” narratives that dominated headlines (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 1). The book, praised by figures like Leon Panetta for honoring unsung public servants, also draws criticism for its evasiveness. What was Davis doing in Lahore? Were the men he killed ISI agents, as some speculated, or just robbers? The Contractor sidesteps these questions, focusing instead on his

Legacy

The Raymond Davis case remains a flashpoint in U.S.-Pakistan relations, a tale of mistrust, violence, and compromise. Davis returned to the U.S., fading from the spotlight, while Pakistan grappled with the fallout. His memoir, published in 2017, seeks to reclaim his narrative, but as he admits, some truths remain “unknown unknowns” (Davis & Reback, 2017, p. 211).

References to The Contractor

- Incident Details: Davis provides a firsthand account of the shooting, emphasizing his self-defense claim and quick draw (p. 14).

- Imprisonment: He describes the psychological toll and absurdity of Pakistan’s legal system (pp. 87-103).

- Diplomatic Resolution: Davis details the diyat deal and rumors of U.S.-Pakistan negotiations (pp. 189-195).

- Personal Reflection: He frames the book as a correction to false narratives and a humanizing effort (pp. 1, 209-211).

- Background: His military and contracting experience is woven throughout, though specifics of his Pakistan role are vague (p. 103).

The book is available from publishers like BenBella Books (ISBN: 9781941631843) and has been reviewed on platforms like Goodreads and Amazon.

Read Also another True Story Javed Iqbal The Serial Killer